The Fight for the word Meat

In February 2018, the US Cattlemen’s Association (USCA) filed a petition with the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) to narrow the definition of ‘meat’. In the petition, the USCA requests that meat and beef be defined as coming from the flesh of an animal that has been raised, slaughtered and harvested in the ‘traditional’ manner. This petition is clearly a reaction to the emergence of cultured meat via cellular agriculture (‘cell ag’) and plant-based meat alternatives.

In other words, the fight for the word meat has begun. The USCA and meat incumbents would clearly feel threatened if cell-cultured meat scales because of the reduced environmental impact (animal agriculture contributes to at least 14.5% of all greenhouse gas emissions) and other factors that may make the public in favour of it, such as cellular agriculture’s impact on animal welfare and the health benefits. And what better way to start the fight by redefining meat as the flesh from an animal raised and slaughtered for it.

Let's Label the Meat

Even before the USCA brought up the idea of what constitutes ‘meat’, there has been discussion about what meat via cellular agriculture should be called. One of the initial names for cell ag products was ‘cultured’, as the products came from cell cultures. Cultured meat. Cultured milk. Cultured leather. All these cell ag products came from cell cultures, shouldn’t the name as well?

The other name that has become popular in 2018 is ‘clean meat’. Shapiro named his book Clean Meat after the term, and many believe the positive connotation and association with clean energy will help the public view meat via cell ag positively. Some have pointed out that there are issues with the name ‘clean meat’, such as implying that conventional meat is ‘dirty’. That may be insulting to farmers and meat producers globally.

Since 2018, more terms and phrases have been explored to describe cell-cultured meat.

Cultured meat or clean meat?

Yet the name of the product shouldn’t be what distinguishes cellular agriculture. What should distinguish cellular agriculture from conventional animal products is the use of a quantitative labeling system.

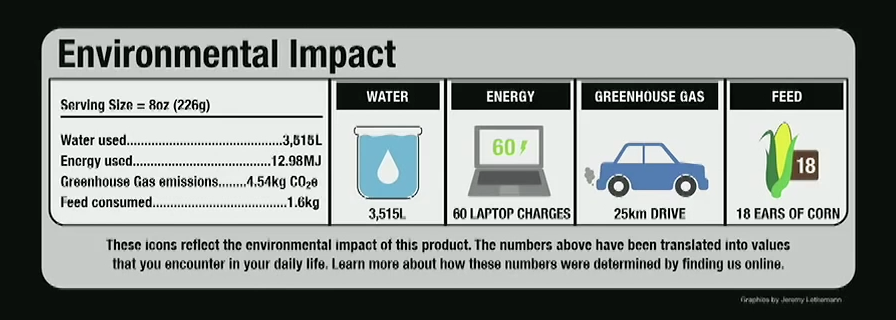

Isha Datar, the Executive Director of New Harvest, shared the idea of quantitative sustainability labels at a TedxToronto talk in 2013. Using quantitative labeling would illustrate the large amount of resources used to produce conventional animal products in comparison to cell ag products, including cultured meat. By presenting the numbers of both products in simple and easily accessible terms, consumers would become more aware of the environmental burden of conventional livestock agriculture and may feel more likely to choose the more sustainable option. Quantitative labeling would also be an improvement from current qualitative ‘sustainability’ stickers. Unless previously aware, qualitative labeling is not enough to motivate consumers who do not know what the stickers represent to alter their purchasing habits.

Photo taken from TedX presentation by Isha Datar: Rethinking Meat at TedxToronto, 2013

After Cape Town declared a ‘Day Zero’ of when the city will run out of water, more cities like Sao Paulo, Bangalore and London are also under threat of running out of water. In these circumstances, how much longer will consumers prefer an 8-ounce steak that required over 3,500 liters of water to produce in comparison to cell ag steak that would require less than a tenth of the water and land used in its production? While there is still a lot of time before a cell ag steak is produced, quantitative labels will ultimately empower the world to make more responsible and environmentally sustainable choices.

Under the Microscope

USCA argues that consumers would be misled by cellular agriculture companies using the word ‘meat’ because that would imply that the product is “derived from animal tissue or flesh for use as food”. Like conventional meat, cultured meat is derived from the same source of cells (stem cells) that give rise to the muscle tissue in animals.

While not grown using animals, cultured meat would be similar to conventional meat under the microscope. Conventional meat consists of animal muscle cells (myocytes), fat (adipose), and connective tissue that adds to the flavor. Cultured meat will consist of the same ingredients: myocytes, adipose and connective tissue. Histologically (that’s the study of tissue structure under a microscope), there would be no difference. If conventional and cultured meats histologically appear similar under a microscope, how can the USCA claim that cultured meat (which derives from the same stem cells that bring rise to conventional meat inside an animal) be excluded from the definition of meat?

Steak: animal muscle tissue, fat, and connective tissue

Conclusion

By consisting of the same animal-derived components as conventional meat, cultured meat is still meat. Yet the USCA is right, perhaps cultured meat should be labelled differently. Refusing to label cultured meat differently would underplay any advantages that cultured meat has over conventional meat. It’s free of antibiotics. It’s free of pathogens. It’s environmentally more sustainable. It’s also free of raising and slaughtering animals in the ‘traditional’ manner.

The cultured meatball from Memphis Meats.

Of course, this shouldn’t mean that cultured meat producers mislead consumers to imply that their products are produced conventionally. Just (formerly known as Hampton Creek) initially plans to release the first cultured meat product by the end of 2018, and other cultured meat companies like Mosa Meat and Memphis Meats plan to release their products by 2021. On that timeline, there is still quite some time to go before cultured meat is at the same scale as conventional meat production. The technology to produce advance meat tissues like steaks are still under development, and, initially, cellular agriculture will complement the incumbent meat industry.

Stay connected with CellAgri

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates weekly from the cellular agriculture industry. Your information will not be shared.